May 28, 2024 – By Zoe Trampke in the Star Press

StarPress Editor’s Note: The following is part of a class project originally initiated in the classroom of Ball State University professor Adam Kuban in fall 2021. Kuban continued the project this spring semester, challenging his students to find sustainability efforts in the Muncie area and pitch their ideas to Ron Wilkins, interim editor of The Star Press, Journal & Courier and Palladium-Item. This spring, stories related to health care will be featured.

Indiana lawmakers remain divided over what steps should be taken to regulate harmful chemicals in Hoosiers’ lives.

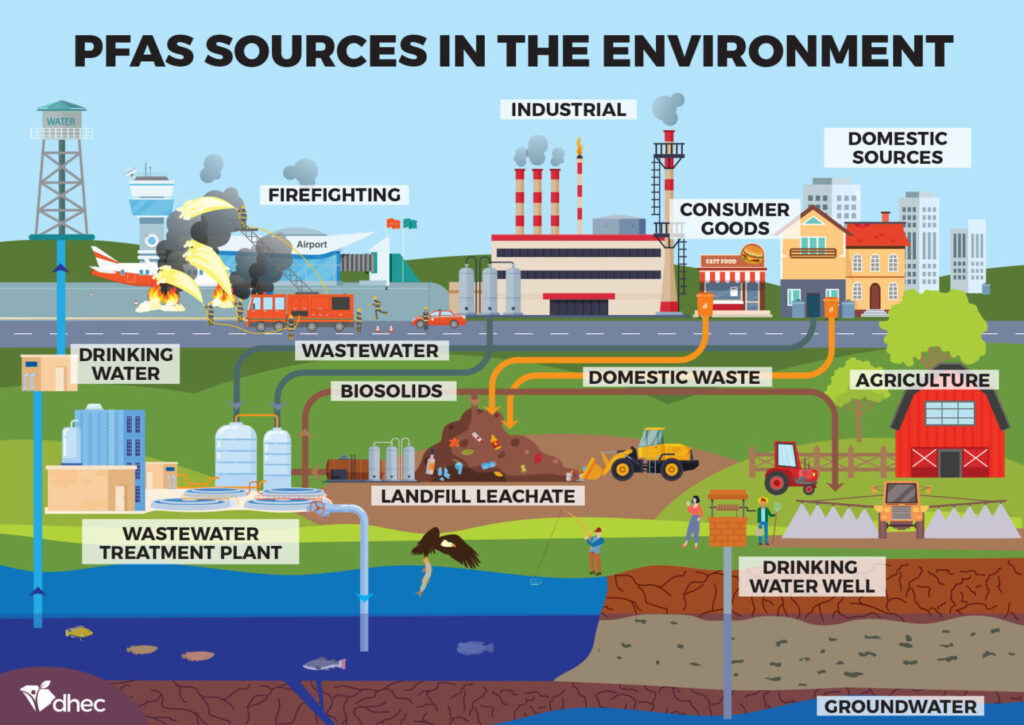

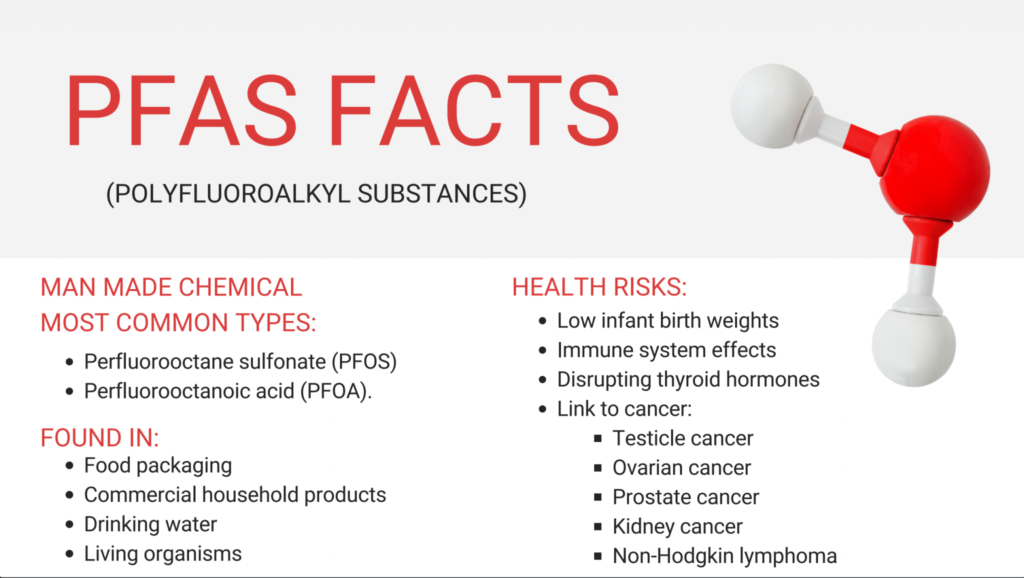

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Science, per- and-polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been shown to have harmful effects on humans and animals. These chemicals became prominent in the 1950s and are found in drinking water as well as other everyday products including non-stick skillets, cosmetic products, waterproof clothing and more.

PFAS have gained public attention in recent years and have been increasingly written about.

In a peer-reviewed article from “Environmental Toxicology Chemistry,” it was found that most published journal articles currently attribute various health issues to PFAS. According to the article, many studies connect PFAS with problems relating to immune function, thyroid function, liver disease and cancer.

The Environmental Protection Agency also considered these chemicals potentially dangerous, warning that these chemicals cause health effects.

Several states, including Michigan and Wisconsin, have enacted drinking water regulations for PFAS chemicals, but Indiana has not.

Rep. Ryan Dvorak (D-South Bend) attempted to pass House Bill 1085, which would have required the Indiana Department of Health to establish state maximum levels for PFAS in water provided by public water systems.

That bill died in committee after failing to advance from the Committee on Environmental Affairs.

While Dvorak has been unsuccessful in passing legislation addressing PFAS chemicals, he says that the attention to PFAS encouraged the Indiana Department of Environmental Management to create a program for testing water supplies across the state. This data is available to the public but has not led to regulation of the chemicals yet.

“The problem is, we know which water systems have PFAS and are sending them into people’s homes, but nothing is being done about them,” Dvorak said. “I’m sure, though, the water systems in those municipalities are trying to figure out ways that they can change it, but there’s no penalties, and the water can still go into people’s homes.”

Dvorak said that part of the problem is that some legislators feel that there is not enough information on PFAS chemicals to justify regulation at the state level. Recently, there have also been changing definitions from the federal government focusing on what would be safe levels should be.

In a peer-reviewed journal article published in “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health” that reviewed differing regulations, it was found that political, social, economic, scientific and practical issues all impact whether PFAS regulation will occur.

The article discusses U.S. Senate Bill 1507 from the 2019 legislative session, which, if passed, would have, “Authorized grants for states to address ‘emerging contaminants’ in drinking water, including PFAS; to direct the U.S. Geological Survey to set PFAS concentration standards in groundwater; to direct the EPA to study, monitor and regulate PFAS in drinking water; and to establish a multiagency initiative to study emerging contaminants, would be $715 million between 2020 and 2024.”

The article notes these high costs seem to impact the decision to regulate.

There are also interest groups that oppose certain PFAS regulations.

Indiana House Bill 1399 recently gained attention because it would have changed the definition of PFAS chemicals to allow for certain products to continue to be manufactured without being labeled as PFAS chemicals. While this bill originally died, there was a last-minute attempted revival. If it had passed, certain chemicals including polymers and gases, which are considered harmful in other states, would have no longer been considered dangerous in Indiana and would not have been recognized as PFAS.

Proponents of Bill 1399 argued that certain essential products contain PFAS that should not be grouped in with other PFAS-containing products.