To keep profits rolling in, oil and gas companies want to turn fossil fuels into a mounting pile of packaging and other plastic products

November 18, 2025 – BY BETH GARDINER EDITED BY ANDREA THOMPSON in Scientific American

In 2018, at a Dubai resort next to the blue-green waters of the Persian Gulf, Amin Nasser, CEO of Saudi Aramco, stood before an audience of hundreds of petrochemical executives to set out his vision for the future of the world’s largest oil company. The goals he described weren’t primarily about energy. Instead he announced plans to pour $100 billion into expanding production of plastic and other petrochemicals.

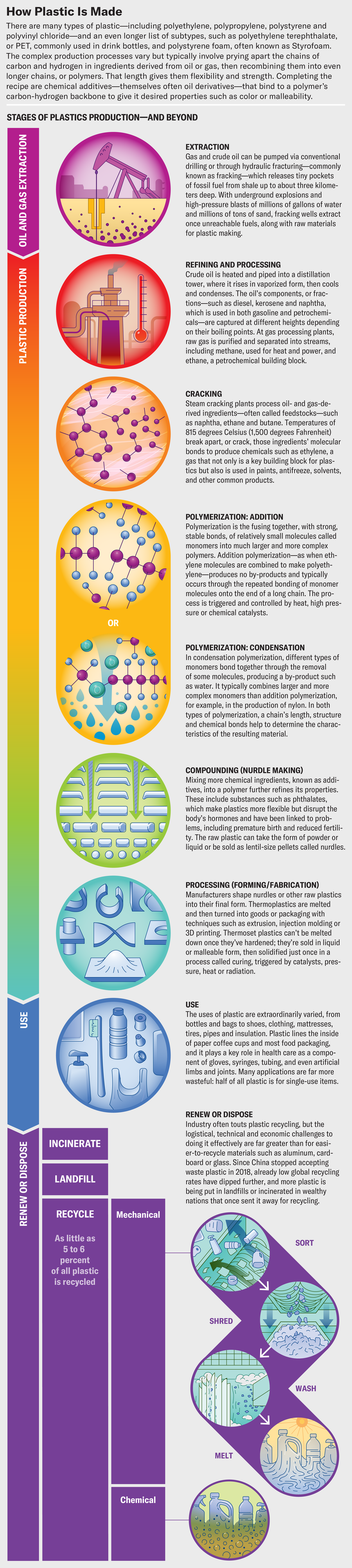

Nasser predicted that with a growing global population wielding more purchasing power every year, petrochemicals—compounds derived from petroleum and other fossil fuels and of which plastics and their ingredients constitute as much as 80 percent—would drive nearly half of oil-demand growth by mid-century. About 98 percent of virgin plastics are made from fossil fuels. In sectors that include packaging, cars and construction, he said, “the tremendous growth in chemicals demand provides us with a fantastic window of opportunity.”

In the years since Nasser’s 2018 speech, Saudi Aramco, owned mainly by the government of Saudi Arabia, has acquired a majority stake in the country’s petrochemical conglomerate SABIC. Together the companies have bought into huge Chinese plastic projects and built petrochemical plants from South Korea to the Texas coast. Aramco aims to turn more than a third of its crude into petrochemicals by the 2030s—a near tripling in 15 years.

Although the industry has framed its plans to pivot to plastic as a response to consumer demand for a material central to modern life, another factor is clearly at play: As the looming dangers of climate change are pushing the world away from fossil fuels, the industry is betting on plastic to protect its profitability. Ramping up plastic and petrochemical output, according to Nasser, will “provide a reliable destination for Saudi Aramco’s future oil production.” As one industry analyst observed of the company’s strategy, “the big picture imperative is to avoid being forced to leave barrels in the ground as demand for transportation fuels declines.”

Even ExxonMobil has acknowledged that electric vehicles’ widespread adoption will probably reduce cars’ need for oil. In one market forecast, the company, already the world’s largest producer of single-use plastics, assured investors that its plans to increase petrochemical production by 80 percent by 2050 will help the industry to pump and sell even more oil at mid-century than it does today.

But there is growing public awareness that all the plastic made for packaging and goods from the absurd to the essential comes at steep costs: the health impacts of the chemicals it contains, the emissions from its production, the mountains of waste that have built up as it is discarded, and the microplastics found everywhere from the most remote corners of the planet to our brains. Some governments have begun enacting legislation, such as bans on certain single-use items, but efforts to deliver more sweeping change hit a wall with the collapse in August of contentious negotiations on a global plastic-pollution treaty. More than 70 nations had pushed for limits on the amount of plastic produced to reduce the flow of waste into the environment. The industry has lobbied heavily against such caps, arguing that improved waste management and recycling are the solution, even though only a small percentage of plastic is currently recycled and many types cannot be recycled by conventional means.

Companies “know they can’t hold their finger in the dike” of an energy transition, says Judith Enck, a former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency official and president of Beyond Plastics, an advocacy group based at Bennington College. “They have to find a gigantic new market, and they have landed on plastic.”

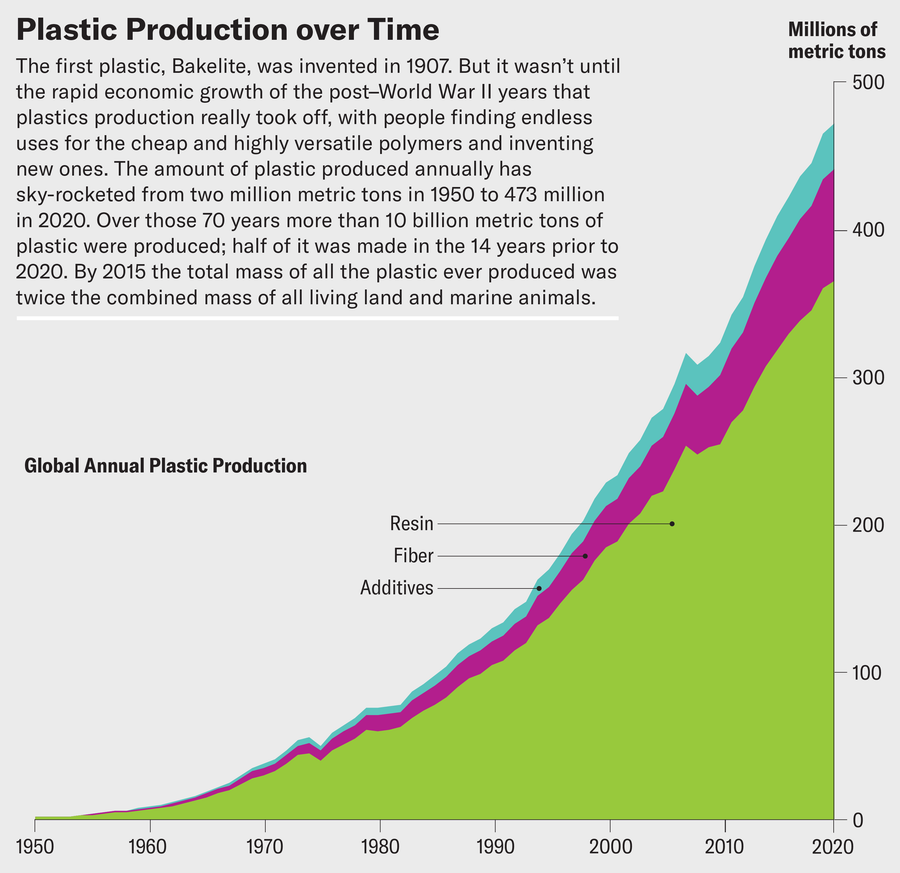

Plastic production has been rising steadily since the end of World War II, when companies poured resources into finding and promoting peacetime uses for a material whose military applications—from nylon parachutes to polyethylene insulation for radar sets—had proved invaluable. Consumers snapped up the flood of new goods and disposable packaging, and the annual output of plastic has climbed from two million metric tons in 1950 to more than 500 million today. A cumulative 8.3 billion metric tons had been produced by 2015, according to a landmark study that was the first to quantify the total amount of plastic created. According to Roland Geyer, an industrial ecologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who co-authored the study, the total has since risen past 10 billion metric tons. About three quarters of all that plastic has become waste, Geyer’s team reported: 9 percent was recycled, 12 percent was incinerated, and 79 percent ended up in landfills or the environment. If current trends continue, 1.1 billion metric tons of plastic will be made annually by 2050—and the cumulative total will be enough, Geyer says, to cover the U.S. in an ankle-deep layer.

Today half of all plastic goes into single-use items, which are often tossed away almost as soon as they’re acquired. A million plastic bottles are purchased each minute, according to the United Nations’ environment agency, and five trillion plastic bags are used every year. In 2016 Americans alone used more than 560 billion plastic utensils and other disposable food-service items.

Plastic, of course, is not just in throwaway packaging. It is a defining, inescapable part of modern life, widely used in construction, clothing, electronic goods and cars. It plays a key role in health care as a component in gloves, syringes, tubing and IV bags, not to mention artificial joints, limbs and hearts. It is also not just one material: there are thousands of types and subtypes, each with its own combination of chemicals that yields desired properties—varying degrees of hard or soft, rigid or flexible, opaque or transparent. One analysis found that 16,000 different chemicals are used in making plastics, including additives such as stabilizers, plasticizers, dyes and flame retardants. More than 4,000 of those substances pose health or environmental dangers, and safety information was lacking for another 10,000, the researchers estimate.

By design, plastic does not readily decompose. Instead it fragments into increasingly minuscule pieces—reaching down to the nanoscale—that have been found just about everywhere scientists have looked. They suffuse the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat. They’ve been detected in blood, semen, breast milk, bone marrow and placentas. Scientists are only beginning to explore what this omnipresence means for the health of humans and the environment, but the signs are worrying. One recent study found microplastics in tissue from human kidneys, livers and brains, and a study of 12 dementia patients’ brains showed greater accumulations than those of people without the disease. Other research found the tiny particles in the neck-artery plaque of nearly 60 percent of patients tested; three years later the rates of heart attacks, strokes and death were 4.5 times higher among people whose samples contained microplastics.

Plastic also exacerbates the climate crisis. The production and disposal of single-use plastics alone creates more greenhouse gases than does the U.K., says the Minderoo Foundation, an Australian research group. That footprint includes the extraction of the oil and gas used to make plastic, the energy-intensive processes for synthesizing it, and emissions from waste that is ultimately burned.

I agree my information will be processed in accordance with the Scientific American and Springer Nature Limited Privacy Policy. We leverage third party services to both verify and deliver email. By providing your email address, you also consent to having the email address shared with third parties for those purposes.Sign Up

Plastic has transformed modern life, bringing once unimaginable convenience as it has penetrated every corner of the global economy. But the consequences of our decades-long plastic boom are not always easy to discern. I wanted to see them up close, starting with the impact on those who live with the dangers posed by plastic’s production.

The behemoth in the global plastics industry is China, the world’s biggest producer of the material. It pumps out around a third of all the plastic currently being made, and it is in the middle of an expansion whose scale the International Energy Agency says “dwarfs any historical precedent.” Over five years, from 2019 to 2024, the agency estimates, China added as much production of ethylene and propylene (two key building blocks of plastic) as takes place in Europe, Japan and Korea combined. Much of the plastic China makes and buys is turned by its many factories into goods exported around the world. Driven by such manufacturing, the country’s voracious demand for finished plastics and other petrochemicals—including the precursors of more plastic—has kept global oil demand climbing even as sales of oil-derived fuels have flatlined.

But since the mid-2000s the fracking revolution that has remade the American energy landscape has also fueled a plastic boom in the U.S. Ethane, a component of fracked gas, is not typically used to generate power or heat. So fossil-fuel and petrochemical companies have poured more than $200 billion into building and expanding U.S. plants to use it, among other fracking by-products, to make plastic and other petrochemicals. Over the course of the 2010s that wave of investment turned the U.S. into a dominant player in the plastic industry.

The heart of U.S. plastic production is found along the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana, where hulking plants covered in spaghettilike tangles of pipes sit beside huge cylindrical tanks in petrochemical complexes that stretch over thousands of hectares. Within those complexes, gas-powered furnaces pry apart the molecular bonds of ethane in a process called ethane cracking, the first step in turning the chemical into plastics.

In the next step of a complex, multistage process, intense pressure and cold turn those fragmented chains of carbon and hydrogen into ethylene, one of petrochemistry’s most important building blocks. Catalysts and more heat then prompt the ethylene to combine with other hydrocarbons to form polyethylene—the world’s most commonly used plastic. A typical polyethylene production plant can make hundreds of billions of lentil-size plastic pellets every day. Loaded onto ships, trains and trucks, they make their way to manufacturers who turn them into toys, bags, bottles, and much, much more.

About 150 such refineries and petrochemical plants crowd the winding 137-kilometer stretch of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. In an area once lined with sugarcane plantations and still home to descendants of the people enslaved there, the plants sit beside flat, wide-open cane fields.

On a sunny January afternoon, I visited Sharon Lavigne in St. James Parish, right across the street from the Mississippi. Her house was easy to find. A big yard sign read, “Formosa Plastics would be a death sentence for St. James,” the words drawn to look as though they were dripping with blood. Lavigne recalls crawfishing, picking blackberries and pecans, and eating vegetables her father grew when she was a child here in the 1950s and 1960s.

Now her grandchildren get rashes from playing outside, and when she opens her front door, she’s hit at times by a smell “so strong it almost would knock you out,” she says. Beginning in the 1960s, the area became home to a growing number of petrochemical facilities, eventually including those making plastics such as polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). They also churn out precursor ingredients, including ethylene dichloride, ethylene oxide, toluene diisocyanate and methanol, which are used in polyester, polyurethanes and PVC. Their emissions include carcinogens such as chloroprene, ethylene oxide and formaldehyde.

In 2018 John Bel Edwards, then governor of Louisiana, announced that Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group (FG) would build a massive $9.4-billion complex three kilometers from Lavigne’s home—12 separate plants, including two ethane crackers and units making polypropylene and several types of polyethylene. Lavigne retired from her job as a special education teacher and started RISE St. James to oppose new petrochemical development because of the health risks it poses to residents in a corridor some call “Cancer Alley.”

The area around Formosa’s site already has more carcinogenic pollution than 99.6 percent of industrial areas in the U.S., a ProPublica analysis found. The project’s permit would allow it to put out more than 5,400 metric tons of air pollution annually, including the carcinogens benzene, formaldehyde, ethylene oxide and 1,3-butadiene. ProPublica estimated it could triple toxic exposures for some residents. “We’re already dying, and if Formosa would come in, we’re going to die even faster,” Lavigne says.

Formosa said that despite activists’ opposition, local support is strong for a plant that would provide 1,200 jobs. “Any claim that FG will greatly increase ‘toxic emissions’ in the area is a misrepresentation and inaccurate,” says Janile Parks, a spokeswoman for FG LA, the conglomerate’s Louisiana arm. If built, the plant will comply with all regulations, she says. “Protecting health, safety and the environment is a priority.”

Although the Biden administration tightened limits on toxic pollutants such as chloroprene and ethylene oxide, enforcement proved short-lived. After appointing two former chemical industry executives to top jobs at the EPA shortly after his inauguration in 2025, President Donald Trump signed a proclamation promising exemptions to dozens of chemical plants. Mass layoffs this year have shrunk the agency, which has shuttered its Environmental Justice office, established to protect those disproportionately harmed by pollution—often low-income communities of color like Lavigne’s. The EPA also announced plans to close a scientific research arm that analyzes dangers posed by toxic chemicals.

Rejecting the “Cancer Alley” nickname, the industry—along with some state and local officials in Louisiana—has argued that average cancer rates in the parishes along the lower Mississippi are close to the statewide average. But finer-grained census-tract data tell another story, according to work done by Tulane Law School’s Environmental Law Clinic, which represents communities fighting pollution. Among poor and predominantly Black neighborhoods, those with more toxic pollution were found to have higher cancer rates. Over a decade toxic pollution had contributed to an extra 850 cancer cases in such neighborhoods, the researchers estimated. “These plants are emitting substances that are known toxins and known carcinogens,” says research scientist Kimberly Terrell, formerly part of the Tulane team. The finding “supports what community members have been saying all along.”That danger is why Lavigne chose to oppose petrochemical expansion in the place where she grew up rather than moving away. When she first heard about Formosa’s plans, she sat on her porch and “asked God if I should leave the land that he gave me. And that’s when He told me, ‘No,’” she recalls. “I think my ancestors are so glad I’m fighting.”

Much of the material being produced along the Mississippi and in other plastic-making regions ends up in the Global South. With wealthy countries already saturated with plastic goods and packaging, industry sees the developing world as its most promising new market. Indonesia, where the use of throwaway packaging is climbing fast, is among the nations at the center of both the industry’s growth hopes and the dangers they pose. It’s also the destination for a great deal of used plastic exported by rich countries, purportedly to be recycled.

To see where some of that material really ends up, I traveled to the outskirts of the archipelago nation’s second-largest city, Surabaya. Just beyond the city limits is Tropodo, a pretty village of narrow streets set amid lush green fields that is known for its small-scale tofu producers. In one open-air tofu factory behind a mint-green home, shredded plastic scrap is piled against walls. When factory owner Muhammad Gufron stuffs some into a big furnace, it crackles audibly. The plastic is fuel, generating steam to heat vats of soy mixture, which workers stir and then scoop into wood draining racks, where it firms into blocks of tofu. “It’s good and cheap,” and it is the fuel for all of Tropodo’s tofu factories, he says.

Heavy black smoke rises from the tall chimneys, almost certainly carrying dioxins, furans, mercury, and other dangerous chemicals that come from burning plastic. The eggs of chickens that peck in Tropodo’s plastic ash contain toxic “forever chemicals” such as polychlorinated biphenyl and perfluorooctane sulfonate, as well as the second-highest dioxin level ever detected in an egg in Asia (the highest was in Vietnam, at a former U.S. military base tainted by the wartime defoliant Agent Orange).

Indonesia has long struggled with plastic pollution. Many areas lack formal waste collection, leaving households to dispose of their own garbage, and a 2020 study found the nation was the world’s biggest source of mismanaged plastic waste. But a significant chunk of its plastic problem comes from waste exported by wealthy countries, including the U.S., which generates more plastic waste than any other nation.

Although Americans toss many of their plastic bottles, yogurt tubs, and other plastic products into recycling bins, as little as 5 to 6 percent of the country’s plastic is actually recycled. The process typically involves shredding sorted material, then melting it into pellets manufacturers can repurpose. But different plastics must be processed separately, and additives such as dyes and plasticizers (which affect the malleability of the plastic) can make effective sorting all but impossible. Even a small amount of missorted material can make a batch unusable. And unlike aluminum, glass or cardboard, which can be recycled again and again, the quality of plastic deteriorates quickly.

Even the easiest-to-recycle types, polyethylene terephthalate and high-density polyethylene—typically used in drink bottles and milk jugs, respectively—often return to market not as new containers but as carpet, clothing or artificial lumber, materials that are not recyclable. There is also little economic incentive to recycle plastic. Recycled plastic can’t compete in terms of either price or quality with cheap and abundant virgin material—and the imbalance only grows as industry ramps up production even further, making new plastic more plentiful and cheaper. All of this is why so much plastic waste ends up in landfills or incinerators.

Still, the U.S. exports about 400,000 metric tons of plastic, ostensibly for recycling, every year. China used to take in much of the world’s plastic waste but stopped accepting it in 2018 because of concerns over air and water pollution from dumping and burning. So Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, were deluged. “We saw many new dumps,” says Daru Setyorini, an Indonesian biologist and activist. “More and more plastic.” Bags and packaging were tangled in branches on riverbanks, piled beside roads, heaped in empty lots and burned in furnaces like the one at Gufron’s tofu factory. That imported waste adds to the flood of plastic entering the seas.

But Indonesia is also dealing with a growing tide of domestic plastic waste. The amount of packaging sold to Indonesians is growing by 4 to 6 percent a year, and flexible plastic packaging—hard-to-recycle soft material used in pouches, films, toothpaste tubes, and bags for snacks and other grocery items—is increasing even more rapidly, says Ariana Susanti of the Indonesian Packaging Federation, which represents companies that make and use packaging. Particularly ubiquitous are sachets, small packets used across the Global South for single servings of everything from shampoo and detergent to spices. One analysis estimated that a little more than a trillion were made in 2023 and predicted that annual output would climb past 1.4 trillion in a decade.

Setyorini has been watching those changes for decades. When she was a schoolgirl in the 1980s and 1990s, she and her mother bought vegetables bundled in newspaper and brought their own baskets, jars and jerricans to the market. Even as the millennium turned and plastic packaging grew ubiquitous, she says, “it was bad but not as bad as now.” Since then, relentless advertisements portraying plastic-wrapped goods as modern, clean and practical have shifted public perception while companies have eliminated alternatives, Setyorini explains. Now “people have no choice,” she says. “They have to buy plastic.”

Setyorini and her husband, Prigi Arisandi, also a biologist, have been measuring the health and environmental impacts of plastic through their nonprofit environmental and research advocacy group Ecoton, which they run from an office nestled among banana and tamarind trees 45 minutes outside Surabaya. They’ve found microplastics in the Brantas River, which provides water for millions of Indonesians, and in the bodies of fish, shrimp and mussels. When they analyzed samples people sent them, they discovered the tiny fragments in everything from soil to breast milk.

Indonesia has been tightening its rules on imported plastic scrap, culminating this year with a ban on foreign plastic waste, although there are concerns about smuggling and enforcement failures. Even so, Setyorini and other activists agree the amount of unrecyclable material arriving today—though still significant—is far smaller than at the peak in 2019. At the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital, Novrizal Tahar, former director of solid waste management, says the country aims to reduce the volume of plastic it leaks into the seas by 70 percent and is more than halfway there already. “This is a good achievement,” he says.

Setyorini acknowledges that improving waste management is important, but she believes Indonesia’s government has focused too much on dealing with plastic after its disposal—through methods such as recycling and processing discarded plastic into fuel for cement kilns and power plants—and not enough on requiring companies to use less of it. She and Arisandi have dragged sachet-covered mannequins to demonstrations to demand that companies stop selling the tiny packets and have sued food and consumer-product firms over their use.

Fundamentally, anything other than reversing plastic’s endless spread and accumulation is, to her mind, a false solution. “We need to go back to that era when people bring their own bag to the market” and vendors refill containers, she tells me—“the old way of shopping” she remembers from her youth.

People opt for single-use plastics not only because they’re convenient but because they’re cheap. They are cheap because the price consumers pay doesn’t reflect the true cost—the expense of managing waste, the environmental damage pollution causes and the growing list of health effects linked to plastic and its associated chemicals. The mounting pile of research detailing these externalities has begun to shift attention toward reducing the amount of plastic we use rather than simply managing waste. With that shift, some governments have started to find ways to achieve that goal.

The European Union has banned single-use plastic items such as utensils, plates, stirrers and straws. In addition, it will require by 2030 that 90 percent of plastic bottles be collected for recycling and that new ones be made from at least one-third recycled material. With a wide-ranging new set of regulations, it’s barring restaurants from providing disposable plastic dishware and cutlery to dine-in patrons, and it’s requiring that 40 percent of plastic packaging used to ship goods to customers or between businesses be reusable by 2030.

In the U.S., local and state governments from Washington, D.C., to Honolulu have passed laws banning certain single-use plastics or requiring they be recyclable or compostable. When designed well, such statutes can make a real difference. New York State implemented a statewide ban on plastic shopping bags in 2020, and in New York City the sanitation department found that the presence of the bags in the waste stream dropped by 68 percent between 2017 and 2023. A different analysis that looked at plastic bag bans in two states and three cities estimated they collectively prevented the use of six billion bags a year.

A handful of states, such as Maine and California, have taken another approach by passing “extended producer responsibility” laws. These laws require manufacturers to help fund recycling programs so the companies that profit from cheap plastics also bear some of the costs of the waste. Such legislation not only eases taxpayers’ burden but also could push companies to rethink the amount and type of packaging they use, experts say. California’s is the farthest-reaching law, giving companies a decade to cut their use of disposable plastic packaging by a quarter. It also requires them to pay for municipalities’ recycling costs and to contribute to a $5-billion fund to address plastic pollution’s harms to health and the environment.

At the global level, more than 180 countries—and reportedly more than 200 petrochemical-company lobbyists—spent three years negotiating a U.N. treaty aimed at addressing the plastic-pollution crisis. After missing a 2024 deadline, the talks went into overtime, but they collapsed this past August; it’s unclear whether they might reconvene. A group of environmentalists and the national delegations supporting them had demanded caps on production, but companies vehemently opposed such limits, focusing on waste management and recycling instead. In session after session, plastic producers fought hard to keep tough measures out of the treaty and stymie progress with procedural obstacles, says Carroll Muffett, former president of the Center for International Environmental Law. “It’s the same strategy we’ve seen play out in the climate space for decades.”

Under President Joe Biden, the U.S. had joined calls for the treaty to limit plastic production, but in February 2025 Trump posted “BACK TO PLASTIC” on social media, referring to his intention to reverse a plan for the government to move toward paper straws. At the treaty talks, the U.S. proposed deleting language about addressing the effects of plastics’ full life cycle and joined other oil- and gas-producing nations in opposing any production caps. In an e-mailed statement, the American Chemistry Council, representing major plastics producers, warned that such caps would bring “significant unintended consequences. The world needs more renewable energy, safe drinking water, energy efficient buildings, and less food waste, which are all enabled by plastics.” What’s more, the council added, such limits would be “ineffective in addressing leakage from inadequate waste management.”

Last year, at a plastics conference in Dubai convened by the Gulf Petrochemicals and Chemicals Association—the same group to whom Saudi Aramco’s chief executive outlined his company’s $100-billion plastic plans nearly six years earlier—Salman Alajmi, a vice president at Kuwait-based petrochemical company Equate, gave the assembled executives an update on the state of the treaty talks. Sentiment has been “getting very emotional against plastic,” he told them. Some of the proposals on the table, he warned, could pave the way for financial penalties that “will diminish for sure the producer economics”—in other words, they would cut into profits.

What’s more, Alajmi told his audience, industry’s critics saw plastic recycling as part of the problem. Alajmi, who was leading a coalition of plastic-producing countries at the negotiations, urged companies to get involved in trying to reshape the deal. “We have to be more proactive,” he said, suggesting they use their legal experts and produce research papers on the benefits of different types of recycling that explain “why they’re safe and why we consider them solutions.”

In two days of panel discussions and PowerPoint presentations at the conference, speaker after speaker shared visions of plastics’ role in a sustainable future through the idea of the “circular economy”—in which discarded material is endlessly recaptured and recycled. Many talked about simplifying packaging to make it more recyclable and scaling up an approach known as chemical recycling, which industry touts as a way to handle plastics that can’t be reprocessed with traditional mechanical methods. Most commonly done via a technique called pyrolysis, it breaks plastics down into their building blocks, ethylene and propylene.

But because of the contamination that inevitably lingers in recycled plastics, to be reused, they have to be diluted into a mixture that’s 90 percent virgin fossil-fuel-derived ingredients. The plastic ultimately created can contain as little as 2 percent recycled material, ProPublica found (although with an accounting method known as mass balance, it can carry labels suggesting a far higher fraction). Pyrolysis can also emit carcinogens such as benzene and dioxins, and the process creates more greenhouse gas emissions than simply producing plastic from oil.

To critics, the petrochemical industry’s argument that recycling will solve the plastics crisis is little more than greenwashing—an attempt to ease consumers’ worries and win acceptance of ever rising production. That’s what Enck, the Beyond Plastics president and former EPA official, told me as we sat on her back porch in the woods outside Albany, N.Y., one sweltering August morning. Producers have “spent millions of dollars lying to the public, trying to get them to believe that [you can] just recycle your plastic and everything will be fine,” she said. California attorney general Rob Bonta alleged as much in a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, saying the company had for decades “deceptively promoted recycling as a cure-all for plastic waste” despite knowing both the conventional and chemical methods “will never be able to process more than a tiny fraction.” (ExxonMobil countersued, accusing Bonta of “blatant misstatements” and defending chemical recycling as “a proven technology” that can keep plastic out of landfills.)

To Geyer, the industrial ecologist quantifying production levels, the bottom line is clear. The only way to manage plastic’s negative impacts is to make and use less of it. “We need to have a talk about the ‘how much,’” he says. “For me, it’s blatantly obvious at this point.”

But an industry profiting from making ever more plastic, Enck says, won’t take the steps needed to get us out of this mess on its own. “The only way to change the trajectory is with strong laws,” she says. If such measures make plastic’s price reflect its true toll, other kinds of packaging—and systems enabling, for example, reusable takeout containers—could compete economically.

On her porch that August day, Enck pulled out a box of smart products and packaging she uses to show visitors what a world with less plastic could look like—paper candy bags that lack the usual plastic coating and are therefore fully recyclable while still keeping contents fresh; a shampoo bar that forgoes the plastic of a bottle; a glass soap pump that you can refill by mixing tablets with water. “This is not rocket science,” she said. And plastic’s beneficial uses are no reason to continue its most wasteful ones. “We can do so much better.”

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the McGraw Fellowship for Business Journalism at the City University of New York’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism.