February 17, 2013- by Mike Williams, News Release from Rice University

Rice University analysis links ozone levels, cardiac arrest. Studies show particulate matter also has direct impact on heart attacks in Houston.

Researchers at Rice University in Houston have found a direct correlation between out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and levels of air pollution and ozone. Their work has prompted more CPR training in at-risk communities.

Rice statisticians Katherine Ensor and Loren Raun announced their findings today at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conference in Boston.

Rice statisticians Katherine Ensor and Loren Raun announced their findings today at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conference in Boston.

Their research, based on a massive data set unique to Houston, was published this month in the American Heart Association journal Circulation.

At the same AAAS symposium, Rice environmental engineer Daniel Cohan discussed how uncertainties in air-quality models might impact efforts to achieve anticipated new ozone standards by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Houston’s air is often smoggy, even more so than Evansville’s, giving it the dubious distinction of being 8th most polluted city n America, according to the American Lung Association for high ozone days.

Given that the American Lung Association has ranked Houston eighth in the United States for high-ozone days, the Rice researchers set out to see if there is a link between ambient ozone levels and cardiac arrest. Ensor is a professor and chair of Rice’s Department of Statistics, and Raun is a research professor in Rice’s Department of Statistics.

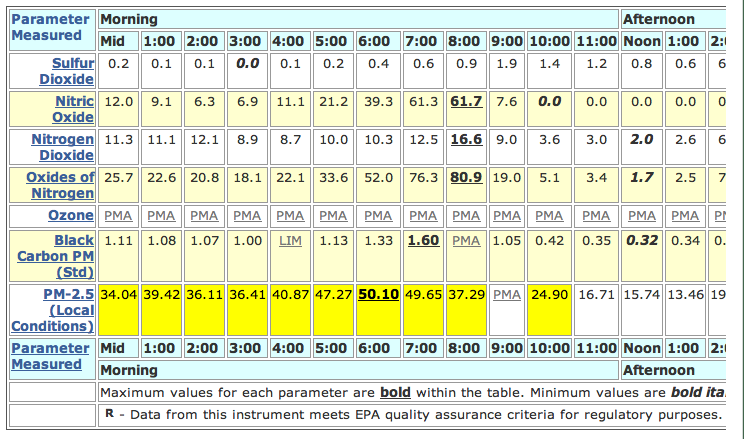

For the new study, the authors analyzed eight years’ worth of data drawn from Houston’s extensive network of air-quality monitors and more than 11,000 concurrent out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) logged by Houston Emergency Medical Services (EMS).

They found a positive correlation between OHCAs and exposure to both fine particulate matter (airborne particles smaller than 2.5 micrograms) and ozone.

The researchers found that a daily average increase in particulate matter of 6 micrograms per day over two days raised the risk of OHCA by 4.6 percent, with particular impact on those with pre-existing (and not necessarily cardiac-related) health conditions. Increases in ozone level were similar, but on a shorter timescale: Each increase of 20 parts per billion over one to three hours also increased OHCA risk, with a peak of 4.4 percent. Peak-time risks from both pollutants rose as high as 4.6 percent. Relative risks were higher for men, African-Americans and people over 65. Continue reading