July 11, 2018, by Nick Swartsell in (Cincinnati) City Beat. For seven decades, the Ohio River Water Sanitation Commission has overseen the health of the roughly 1,000-mile-long waterway that provides drinking water to more than 5 million people. But it may soon shed many of its pollution standards.

Recreational use of the Ohio River is often overlooked by decision makers when it comes to water quality. Now, some fundamental protections for recreational users may be taken away by the very multi-state Commission that is supposed to protect us. Photo © 2014 BlairPhotoEVV

Two decades before the Environmental Protection Agency, an eight-state commission looked out for the health of the nearly 1,000-mile stretch of water that defines Cincinnati and provides more than five million people with drinking water. But it could soon walk back from a key part of that role.

Residents of Greater Cincinnati and elsewhere will get to weigh in later this month as the Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission, or ORSANCO, takes final steps to back away from many of its pollution control standards it has provided states along the river.

A majority of the commission says many of the standards are redundant — rules from federal and state agencies are currently keeping water quality in the river at the level ORSANCO wants to see independent of its criteria. But critics of the proposal say a significant number of the standards aren’t duplicated by federal or state agencies and that the commission needs to continue doing everything it can to ensure water quality, especially as the Trump administration works to roll back environmental regulations.

The commission began a regular review process of its standards back in January with an ad-hoc committee and calls for public input. Now, before the commission formally adopts its rollback on pollution standards, it is holding another round of public input, including a public hearing July 26 at the Holiday Inn near Cincinnati International Airport in Erlanger, Kentucky.

Formed in 1948, Cincinnati-based ORSANCO has worked to make the Ohio River clean and safe in part by setting standards for the maximum levels of various pollutants in the river. The commission’s standards have long been used by states to ensure that the Ohio River is clean enough for recreation, drinking and other uses.

But now commissioners say that the federal EPA, founded in 1970, the 1972 federal Clean Water Act and state environmental agencies have made those standards redundant.

“The commission is considering this because, the thought is, with the robust state programs and the U.S. EPA’s program, there are better uses of our resources than really having a potentially redundant third layer of standards,” ORSANCO Executive Director Richard Harrison told WVXU earlier this year. “Our compact is not changing. I’m confident that our commission is not going to move forward with something that will harm the water quality of the Ohio River.”

Some environmental groups, and a minority of the commission, however, strongly disagree. Some commissioners with ORSANCO have expressed “grave concern” with the move and argue that eliminating the body’s standards when it comes to ambient levels of various pollutants can only hinder efforts to maintain and improve the river’s health.

Recreational use of the Ohio River could be jeopardized if all pollution standards for the River are given to the various states. Indiana and Kentucky have both shown lax enforcement of standards in the past and ORTSANCO currently provides an extra layer of protection for water quality standards. Photo© 2016 BlairPhotoEVV

“ORSANCO, as a federally-sanctioned compact among several signatory states, possesses a degree of insulation from the vagaries of the political process, and is able to research, develop, propose and adopt standards tailored to the specific needs of the river in an atmosphere that stresses sound science and data-driven policy,” dissenting commissioners said in their minority report opposing the elimination of the rules.

The minority cited recent moves by Congress and the Trump administration that they say raise concerns about commitment to environmental protection. The elimination of the federal Stream Protection Rule and proposals by the EPA to revise guidelines for what counts as protected bodies of water, they say, “reflect that the standards and scope of the Clean Water Act and regulations adopted pursuant to that Act are neither static, nor necessarily as broad or protective, as might be needed to address the specific needs of the Ohio River Basin.”

There are roughly 600 permitted companies and other groups discharging into the Ohio River. The federal Clean Water Act, administered by the EPA, recommends maximum levels of pollutants these entities are allowed to discharge. States, however, make their own standards, which the EPA then approves.

ORSANCO’s standards exist alongside those state standards. While the state guidelines generally regulate what is coming specifically out of dischargers’ pipes, the commission creates guidelines for ambient pollution levels in the water as a whole.

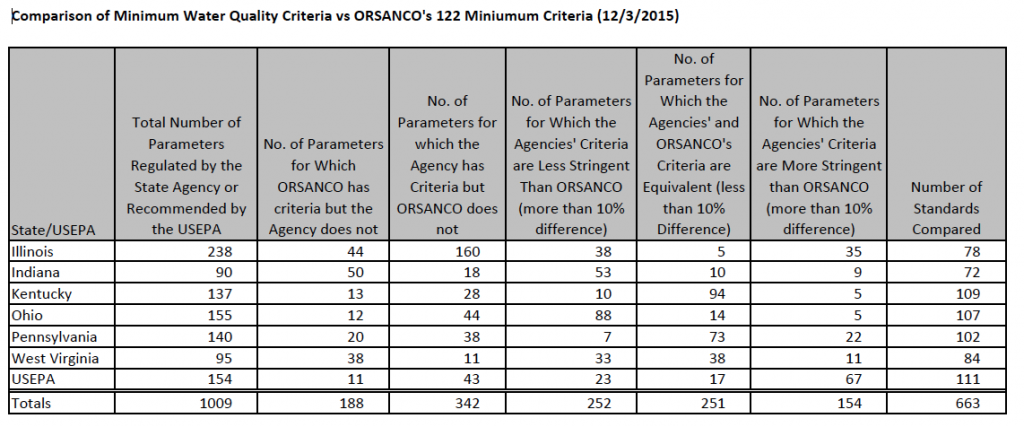

While commissioners supporting a rollback of ORSANCO’s pollution standards say that the state guidelines largely achieve goals for pollution reduction on their own, dissenting commissioners point out that there are 188 instances in which ORSANCO has set pollution criteria that six of the member states and the federal EPA don’t have. Simply relying on the state and federal EPA standards “may not be adequate to protect the aquatic life and uses of the Ohio River,” the dissenting commissioners wrote.

ORSANCO is made up of 23 commissioners, with two or three each tapped by the governors of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, the states the river flows through, as well as two others appointed by the federal government.

Most of those appointees have had long careers with state EPAs, regional water conservancies or other environmental groups. One of the federal government’s appointees is George Elmaraghy, who served at the Ohio EPA for nearly four decades. Elmaraghy was chief of its surface water division when he was asked to resign by Gov. John Kasich in 2014 after opposing mining permits sought by coal companies in the state.

A small minority of the commission, including West Virginia’s David Flannery and Ronald Potesta, however, are also industry consultants or attorneys who have represented industrial clients in matters around environmental regulations. Potesta, whose consulting firm works with a gamut of clients from nonprofits to companies in the mining, manufacturing and chemical industries, chairs the commission.

The potential shift away from ORSANCO’s pollution control standards comes as the commission undertakes its usual triennial review of those guidelines. Earlier this year, an ad-hoc committee of commissioners reviewed those rules, as well as solicited public feedback about them, and came up with five possible actions ORSANCO could take.

The first would have eliminated all pollution standards the body sets. The second, called Alternative Two, was the one recommended by the committee and approved by a majority of the whole commission. That alternative would step back from a substantial number of ORSANCO’s standards around pollution control.

The draft proposal for this set of standards shows whole chapters of pollution control regulations crossed out in red, with a few new passages added in. For the most part, it guts ORSANCO’s role as an agency regulating discharge into the Ohio River.

ORSANCO Executive Director Harrison points out, however, that the commission does a number of other things with a small staff of just 20 employees — public outreach, spill mitigation and response, river cleanups, monitoring of fish and insect health and population, and other efforts.

“It’s important that our resources are used wisely,” Harrison said. “We have to make sure that our programs are providing the best value to our partners. This is something that has been thoroughly reviewed. The commission has been very transparent. We’re approaching this as a very transparent, objective process.”

But some environmental activists say ORSANCO needs to stay the course. Rich Cogen is the executive director of the Ohio River Foundation, a Blue Ash nonprofit founded in 2000 to preserve and improve the quality of the river. He says that not all states have equal ability to set their own standards alone as stipulated by the Clean Water Act.

“Without ORSANCO’s standards all Ohio River states will have to develop their own standards, which may very lead to interstate litigation as downriver states fight to protect their water quality that might be jeopardized by weaker upriver state standards,” Cogen says. “ORSANCO is not working well in the defense of the river and the 5 million people who depend on it for their drinking water. They should be working with all the states collaboratively for uniform standards for all water quality standards. Instead they are throwing up their hands and inviting multi-state chaos.”

Other activists are concerned about the erosion of another layer of protections as the Trump administration peels back federal environmental regulations.

“I think it’s critical that ORSANCO be the cheerleader, the advocate, the folks who go to the mat for keeping the Ohio River clean and getting it even cleaner and holding the states and the federal EPA accountable,” former Green Umbrella Executive Director Brewster Rhoads said earlier this year. “This is somewhat political, I get it, but we’ve had a change in administration and folks at the helm of the U.S. EPA and some of the state EPAs who frankly are not into the concerns… of the average citizen who cares about clean water. I would hope that ORSANCO would do everything it humanly can to monitor and blow the whistle when folks are not meeting the basic standards and frankly championing higher standards whenever it’s possible.”

I strongly support ORSANCO’s unified single purpose protection of the Ohio River and the continued provision of clean water for the multi-state people who depend on it. ORSANCO should be working with all the states collaboratively for uniform standards for all water quality standards, instead of subjecting clean water to the whims of myriad differently capable State entities thereby inviting multi-state chaos, as suggested by Rich Cogen and Brewster Rhoads. It is a misnomer to label “the elimination of duplication” at the ORSANCO comprehensive level of standards in exchange for partial, different, incomplete and varying standards at the various multi-state levels, and expect maximum uniformity of standards and comprehensive administration of the provision of clean water.

.