October 9, 2021 – by Susan Thomas in the Chicago Tribune (paywall)

As her state of disbelief quickly turned to outrage, Susan MiHalo watched an orange plume of murky discharge expand from the U.S. Steel Burns Harbor outflow into Lake Michigan. Residents and boaters had seen the spill early that afternoon of Sept. 26, but were unsure of who to call. There were no signs along the waterway with this emergency information. By the time MiHalo, chair of the Ogden Dunes Environmental Advisory Board (ODEAB), was alerted and started making emergency calls, hours had passed. Within one hour of her first calls, the National Park Service arrived on the scene and promptly closed all area beaches out of an abundance of caution.

As her state of disbelief quickly turned to outrage, Susan MiHalo watched an orange plume of murky discharge expand from the U.S. Steel Burns Harbor outflow into Lake Michigan. Residents and boaters had seen the spill early that afternoon of Sept. 26, but were unsure of who to call. There were no signs along the waterway with this emergency information. By the time MiHalo, chair of the Ogden Dunes Environmental Advisory Board (ODEAB), was alerted and started making emergency calls, hours had passed. Within one hour of her first calls, the National Park Service arrived on the scene and promptly closed all area beaches out of an abundance of caution.

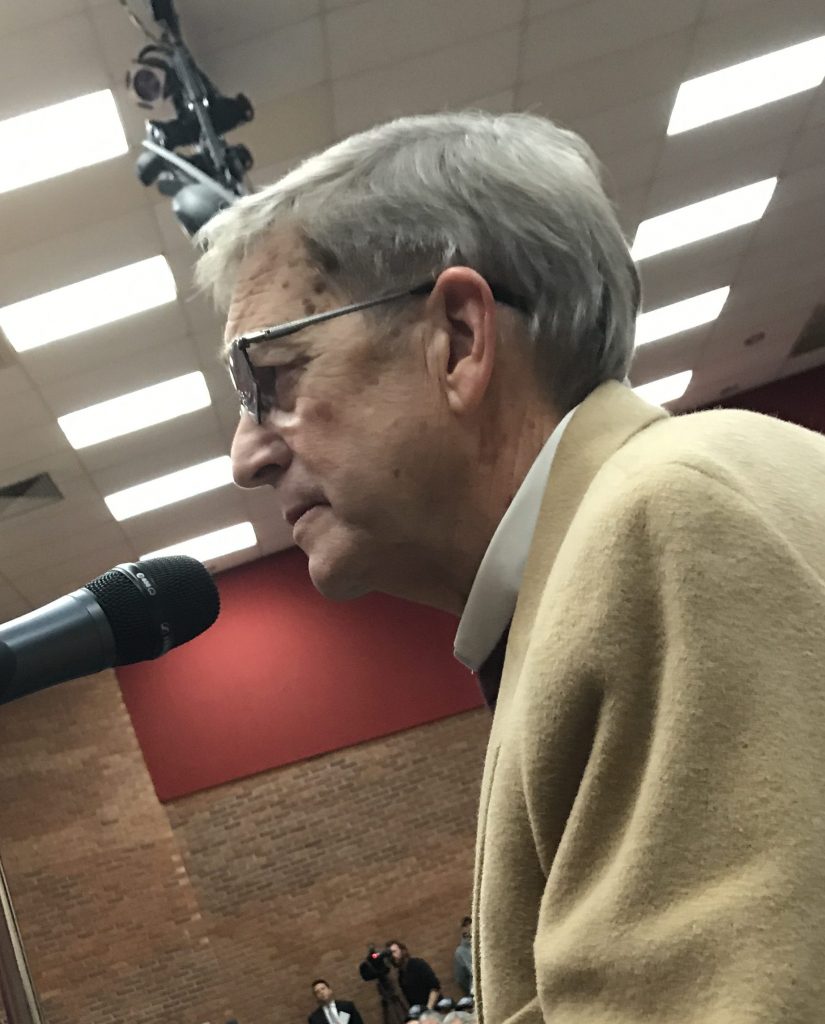

Contrast that to the time it took the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) and United States Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 (EPA) to show up at the scene: it was almost 8 p.m. and the precious hours to contain the spill were lost. While an anxious public panicked over what could be in that orange plume, U.S. Steel, IDEM and EPA had no comment on the substance for several days — a gut punch of a response, considering only weeks earlier IDEM Commissioner Bruno Pigott vociferously assured attendees at a public comment hearing that IDEM was taking its severe emergency communication problems with industry and area towns “very, very seriously,” while granting U.S. Steel another five-year permit in spite of hundreds of violations and legal actions against the mill.

That very public hearing was for a National Pollution Discharge Elimination Systems (NPDES) permit renewal for another area steel mill Cleveland-Cliffs, formerly ArcelorMittal, whose 2019 toxic ammonia and cyanide spill into Burns Harbor was ignored by industry and IDEM until thousands of dead fish surfaced four days after the spill. Throughout that time, residents of Ogden Dunes and visitors to the National Park continued to recreate in the lake, including drinking and bathing in that water. There was no emergency response. In contrast, Ogden Dunes Town Council President Doug Cannon literally ran down to the beach himself to call people out of the water. For area residents, the U.S. Steel spill was a bitter repeat of those events of only two years prior.

By the time that 2019 catastrophic spill happened, ArcelorMittal had already broken Clean Water laws more than 100 times, according to a lawsuit filed against them by the Hoosier Environmental Council and the Environmental Law and Policy Center.

By the time that 2019 catastrophic spill happened, ArcelorMittal had already broken Clean Water laws more than 100 times, according to a lawsuit filed against them by the Hoosier Environmental Council and the Environmental Law and Policy Center.

Bianca Passo, also of Ogden Dunes ODEAB, said “Each time an industrial spill occurs, our town is forced to close the beach and Indiana American Water must shut off the Ogden Dunes drinking water intake. Each time an illegal discharge occurs we feel like we are playing a game of roulette, wondering what type of toxic chemical might be dumped next.”

Residents, area business, and the $500 million tourism industry in Northwest Indiana have plenty of reasons to be nervous. U.S. Steel just signed a consent decree this September intended to prevent future illegal discharges, in reaction to their 2017 toxic hexavalent chromium spill (that flowed the same route into Lake Michigan as their Sept. 26 spill, which was finally identified days later as a permitable amount of iron). U.S. Steel was also required to pay a civil penalty of $601,242 and reimburse government agencies for $625,000, plus pay $600,000 over the next three years for testing the lake and its connected waterways. In May, IDEM fined U.S. Steel $950,000 for more than 25 permit violations from 2018-2020. Unfortunately the monetary sum of their penalties is no deterrent — it’s an actual bargain for U.S. Steel, whose record profits this year were recorded in excess of $1 billion. U.S. Steel’s history in environmental violations is vast in other states as well: Between 2018-19 alone they violated the Clean Air Act more than 12,000 times according to a lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania.

Days after the Sept. 26 spill, area outrage finally reached a tipping point, which has grown in volume since the spill was followed by an oil spill from U.S. Steel Midwest earlier this week. Spearheaded by Save the Dunes, a coalition of more than 25 organizations including environmental groups, local governments and agencies, residents associations, and recreation and sporting groups convened for an emergency meeting. Subsequently, they sent a letter to Governor Eric Holcomb and IDEM Commissioner Pigott demanding stiffer monetary penalties, heightened scrutiny, and vigorous enforcement against chronic polluters. They also demanded pollution control and communications requirements be strengthened in future NPDES permit renewals with further review of IDEM’s permitting process, and more thorough support for IDEM, which lost $35 million in budget cuts over the last decade leading to staffing issues.

“Over the last several budget cycles IDEM and the Department of Natural Resources have been sorely underfunded,” says retiring State Senator for the region’s lake shore districts Karen Tallian, D-Ogden Dunes. “With the budget surplus we have now, there is no excuse. Indiana needs that money to get back in the fight to protect our environment.”

IDEM permitting allows industry to self-monitor/self-test, leaving the fox to guard the hen house. It was a whistleblower, not IDEM, revealed repeated fraudulent testing from ArcelorMittal following the 2019 spills. It is worth noting that the emergency coalition was not convinced the Sept. 26 spill was “harmless” iron. Though EPA and IDEM approved the results, it was U.S. Steel who conducted the tests. At the federal level, EPA Region 5, that serves Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, Minnesota and 35 Indigenous Tribes, only has an acting director but no one to officially fill that job yet after budget cuts hampered its effectiveness during the Trump years. It’s also seen as a free pass to industry polluters.

Economy and environment linked

Unless immediate emergency actions are taken for area industry to obey the Clean Water Act and environmental laws, we are headed toward a state where gross domestic product revenues, property values and taxes will plummet with each passing spill. Continue reading →

Plastic

Plastic